The Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran Caves

Nestled along the Dead Sea’s northwestern shore, the Qumran Caves are renowned for housing the Dead Sea Scrolls — ancient manuscripts that illuminate Jewish life during the Second Temple period. Believed to be inhabited by the Essenes, a sect devoted to religious study and purity, these caves offer profound insights into early biblical texts and traditions.

Written by Zvika Gasner Koheleth, 12-December-2024 (Originally 04-March 2022). Photography by Angela Hechtfisch

The Qumran Caves, located on the northwestern shore of the Dead Sea near Kalia Beach and Kibbutz Kalia, are one of the most significant archaeological sites in Israel. These caves were home to a Jewish sect, believed to be the Essenes, who lived there between 150 BCE and 68 CE. This settlement, consisting of approximately 100 to 150 young, single men, was likely part of a strict, ascetic community devoted to religious study and ritual purity. Jewish residents abandoned the site just two years before the Romans destroyed the Second Temple—and five years before Masada, the last Jewish stronghold, fell.

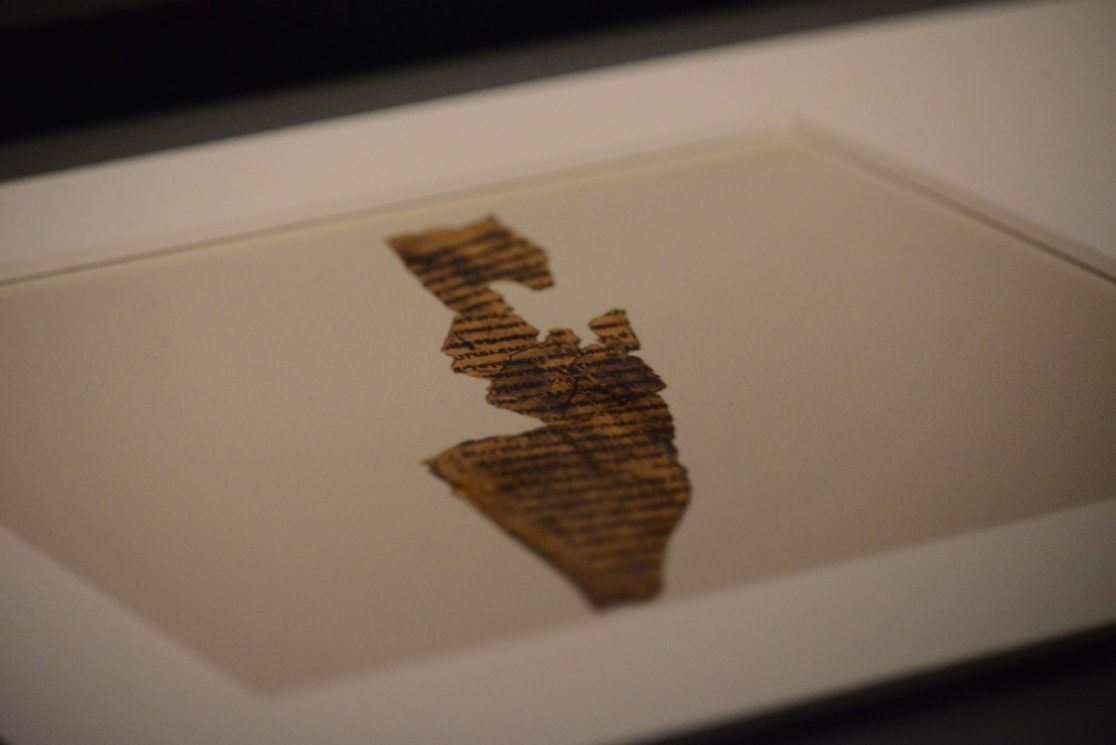

The Qumran Caves gained global fame when archaeologists discovered the Dead Sea Scrolls—ancient manuscripts written mostly in Hebrew, with some in Greek and Paleo-Hebrew. Scribes wrote these scrolls, mainly on leather, during the Second Temple period, and they’ve remained remarkably well preserved.

A modern Hebrew speaker can still read most of these texts, which include 929 biblical manuscripts nearly identical to the Hebrew Bible used today. This makes them the oldest known biblical documents, except for a seventh-century BCE priestly blessing (“Cohanim Blessing”) engraved on copper, discovered in 2022 in the “City of David” (biblical Jerusalem).

Beyond biblical texts, other scrolls reveal insights into the daily life, beliefs, and customs of the Qumran community, known as the Yahad society, meaning unity in Hebrew. A third category of scrolls contains mystical writings, prophecies, and apocalyptic visions, describing a great cosmic battle between the Sons of Light, representing the Qumran sect, and the Sons of Darkness, symbolizing the forces of evil.

The Qumran Caves remain a crucial key to understanding Jewish history, early biblical texts, and the religious landscape of the Second Temple period.

The Yahad society at Qumran

The Yahad society followed an extremely strict daily routine, functioning as a self-sufficient community with no private possessions. Members lived a life of discipline and simplicity, dedicating themselves to religious study and purification. Twice a day, they immersed in ritual baths, known as mikveh, to cleanse both body and soul. They filled these baths with water from an elaborate aqueduct system they built—still standing today. Their practice was based on the biblical verse from Ezekiel 36:25:

“And I will sprinkle clean water upon you, and ye shall be clean; from all your uncleannesses, and from all your idols, will I cleanse you.”

This purification tradition was similar to the ritual washing performed in Jerusalem before entering the Temple. The Yahad community prioritized studying and copying biblical texts, constantly reading and interpreting scripture. They followed a strict 24/7 rotating schedule for study, as commanded in Joshua 1:8:

“This book of the law shall not depart out of your mouth, but you shall meditate on it day and night, that you may observe to do according to all that is written therein: for then you shall make your way prosperous, and then you shall have good success.”

This devotion defined their identity and purpose.

Years later, researchers discovered the scrolls and found only the Book of Joshua in its entirety, measuring 743 centimeters in length. This is symbolic, as the prophet Joshua extensively addressed themes of the End of Time and the final battle of Armageddon.

The Second Temple period marked a significant shift in Judaism—from a religion centered on animal sacrifices to one focused on studying and interpreting holy texts. This transformation led to the Jewish people being recognized as the “People of the Book.” Additionally, one of Judaism’s fundamental innovations—the establishment of fixed daily prayers—originated in Qumran. This practice has been preserved in Jewish tradition to this day.

The discovery of Dead Sea Scrolls

A Bedouin shepherd boy accidentally discovered the Qumran caves while searching for a lost goat. He tossed a stone into the cave, and the sharp ricochet instantly alerted him to something hidden inside. In 1947, he found the first three scrolls lying inside clay jars, along with sheets, coins, and other archaeological treasures. Recognizing their importance, an Arab collector acquired them, and on November 29, 1947—the same day the UN voted for Israel’s independence—Professor Eleazar Sukenik of Jerusalem University purchased them.

Over the next few years, smugglers took four more scrolls out of Israel, and Professor Yigal Yadin—son of the original buyer and former IDF Chief of Staff during the 1948 War of Independence—later bought them in New York. Further excavations, mostly in the early 1950s, uncovered a total of 929 scrolls in 11 caves, each varying in quality and condition. These discoveries remain among the most significant in biblical archaeology.

Theory on the origins of the Dead Sea Scrolls

Who were the people of Qumran? Were they strict Jews of the Tzadok sect, members of the Jewish priestly families of Jerusalem, a group of Essenes who embraced modest living, or even an early Christian monastic order?

Some scholars support the latter theory, noting similarities between the words of Jesus in the New Testament and passages found in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Additionally, many of the scrolls date to the time of Jesus’s life. Early Christian believers may have written parts of the scrolls, as they included certain biblical texts—like the Book of Judith—that appear in Christian scriptures but not in the Jewish Bible.

Some scholars suggest that people in Jerusalem wrote the scrolls and later hid them in Qumran for safekeeping. Some believe that Jewish priests smuggled the manuscripts out of the city just before the Second Temple’s destruction in 70 AD. This theory is based on the vast number of texts discovered—929 scrolls—which seems too large for the relatively small population of Qumran to have produced alone.

Whether written by Qumran’s residents or transported from Jerusalem, the scrolls remain one of the greatest archaeological and historical treasures, shedding light on early Judaism and its possible connections to Christianity.

The Qumran Scrolls Trail

Many travelers and guides highly recommend exploring the Qumran site—especially on foot. In 2021, authorities officially opened the Scrolls Trail at Qumran National Park, offering a stunning desert hike. They dedicated the trail to archaeologist Hanan Eshel, a leading expert on the Second Temple period and the Qumran caves, particularly Caves 1, 2, and 11, located north of the park.

The trail is divided into two sections. The longer, green-marked North trail is 2 km and begins at the northwestern border of Kibbutz Kalia, taking over an hour. The shorter, blue-marked South trail is 1 km, starting at the Kibbutz Cemetery and taking around 30 minutes. Both routes provide breathtaking views of Cave 1, the location where the first Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered. Visitors should not attempt to climb into the cave.

During our visit, we spotted a group of 50 ibexes roaming the slopes. The scenery is spectacular, and the trail is mostly flat, with some wooden stairs. However, it is not a circular path, meaning visitors must walk back to their starting point, effectively doubling the distance.

Important: Under no circumstances should you enter the caves, both for safety reasons and to protect the bat population living inside.

The theory of “Covenant Renewal Ceremony” by Daniel Vainstub

A recent theory about Qumran, published in August 2021 in Religions magazine by Daniel Vainstub of the Department of Bible, Archaeology, and Ancient Near East at Ben-Gurion University, offers a new perspective on the site’s purpose. While still associating Qumran with the extreme Jewish Yahad sect (often linked to the Essenes), Vainstub challenges the idea of a permanent settlement based on archaeological evidence.

Findings at the site include a massive refinery, two large ritual purification pools (mikvaot), eight smaller mikvaot, and a cemetery outside the village walls—consistent with Jewish purity laws. Archaeologists found no private homes, public buildings, or fortifications, which raised doubts about a stable year-round community living there.

Vainstub proposes that Qumran served as a temporary gathering site rather than a permanent village. He suggests it hosted the annual Covenant Renewal Ceremony during the festival of Shavuot, where members of the Yahad sect would assemble for religious rituals. The ceremony, he argues, was the primary reason for Qumran’s architectural development.

Thus, Qumran was only occupied once a year for a short period during Shavuot, remaining largely deserted for the rest of the year. This theory challenges earlier assumptions and redefines Qumran’s role in Jewish history.

The Dead Sea Scrolls hold immense historical and national value. Thanks to the Judean Desert’s dry air and the darkness inside the Qumran caves, nature preserved them for nearly 2,000 years. Today, the Israel Museum in Jerusalem houses them in the Shrine of the Book, where curators display them in a carefully controlled mini-ecosystem to ensure their preservation for future generations.

The “Shrine of the Book” in Jerusalem

The Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem is one of the most significant places to visit when learning about the Dead Sea Scrolls. It is undoubtedly the second essential part of the story you cannot miss. A visit to the Shrine of the Book, where these ancient manuscripts are preserved and displayed, is a crucial step in understanding their historical, cultural, and religious significance.

First, the architecture of the museum itself is deeply symbolic. The striking white, water-shaped dome represents the ongoing spiritual and philosophical tension between the “Sons of Light” and the “Sons of Darkness”—a central theme in the scrolls. Architects designed the structure to resemble the clay amphorae jars that once held the scrolls in the Qumran Caves. To enhance the experience, they crafted the entrance to feel like stepping into an underground cave, fully immersing visitors in the discovery’s historical setting.

Curators preserve the scrolls under carefully controlled conditions. They store them in a dry, cool environment to prevent deterioration and rotate them every three months to reduce light exposure. This delicate process ensures that the fragile documents, which date back over 2,000 years, remain intact for future generations to study. Even visitors with a basic understanding of Hebrew can appreciate the linguistic and historical richness of these texts.

The Shrine of the Book is part of the Israel Museum, located on Ram Hill in Jerusalem, next to the Israeli Parliament (Knesset). Its placement underscores the national and global significance of the Dead Sea Scrolls, which provide unparalleled insights into Jewish history, religious thought, and early biblical texts. For scholars, historians, and curious travelers alike, this exhibit is a must-see—a true gateway to the past.

The “Keter” codex at the “Shrine of Books”

On the lower level of the Shrine of the Book, visitors can explore one of the most precious biblical artifacts in existence—the Keter Codex, the oldest complete handwritten canonical Hebrew Bible. Jewish scholars have considered it one of the most authoritative versions of the biblical text since the early 9th century, using it to shape scholarship for generations.

This codex has a fascinating journey. Scribes originally wrote it in Tiberias, Israel. Later, scholars brought it to Cairo, Egypt, where Maimonides (Rambam) used it for his biblical interpretations. From there, it moved to Aleppo, Syria, earning the name “Keter Aram Tzova” (Aleppo Codex). Caregivers safeguarded it for centuries before finally bringing it back to Jerusalem, where it remains today.

Now housed in a controlled environment, this manuscript stands as a historical, religious, and cultural treasure, preserving the Bible’s authentic text for the world.

General Information

Jerusalem is only 20 minutes drive from the caves of Qumran. Tickets for the Qumran national park for an adult are 45 IL shekels and for the “Israel Museum” are 55 shekels. both places operate 7 days a week. Audio guide in English for the Qumran caves are available for 10 Shekels. A preferable option for overnight in the area could be either one of Ein-Bokek Dead Sea hotels or one of Jerusalem’s finest.

A link to the new sensational discoveries of the Qumran scrolls announced on March 2021 is attached here.